The Evolution of the English Language

Languages both change slowly and change all the time and English is no exception. The term ‘English’ comes from the Angles and the language which now dominates world culture began life as a dialect of German. Then the Normans landed and added an element of French. Latin, the language of the church, was also part of the mix as it is the language of formal proceedings.

History and Language: Conquests and Population Shifts

The Anglo-Saxons became the underclass once the Normans arrived and so words from an Anglo-Saxon root tend to be considered quite coarse today (e.g. F word and ‘twat’). Words from a French root, the language of the court, tend to be more formal, for example ‘sincerely’. Words from a Latin root are often academic or professional, for example ‘legal’, ‘obstructive’.

Anglo-Saxon English (Old English) is not intelligible to most modern English speakers without some training and/or a glossary. Middle English, the form of English which followed the Norman Conquest, makes sense when read aloud. At this point in history there was no standardised spelling (that came with Samuel Johnson’s dictionary in 1755, the first ever English dictionary) so words were spelled phonetically, hence ‘dayes’ would have been pronounced day-es which in modern English has become ‘days’.

Early Modern English was the next point in the language’s evolution and followed the English Renaissance, the artistic and cultural movement which began when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field on 22nd August 1485 and became Henry VII. The Tudors, particularly Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, were patrons of the arts and we have many surviving texts from their reigns to preserve the language of their era. We most read Early Modern English today via Shakespeare whose work keeps it alive in the public consciousness. It is comprehensible to a 21st century English speaking audience, although some words may need explaining, for example ‘wherefore’ means ‘why’ so when Juliet asks, ‘Wherefore art thou Romeo?’ she means, ‘Why are you Romeo?’ rather than ‘where are you, Romeo?’. ‘Whence?’ means ‘from where?’, not when.

This period saw the invention of the Gutenberg press and more and more people were able to own books and so the written language changed and evolved to include more vernacular and not just sacred and heroic texts with the corresponding use of language.

Over time modern English abandoned the informal form of you (thou/thee) and adopted the same word for the singular and plural second person: ‘you’. The ending of verbs changed and we no longer said things like ‘thou goest’ and ‘she didst’.

The 1755 dictionary introduced standardised spelling as English, both written and spoken, continued to develop.

Today English is ever evolving as technology changes. Words and phrases like ‘search engine’ and ‘WiFi’ did not exist when I was at school! We also see the change in use of words, for example ‘literally’. This is my pet hate- I once heard an interview where someone said, ‘I literally had a heart attack’ – yet she meant the phrase figuratively and was in perfect health. This is what happened in the past to the word ‘actually’ which used to mean that something had factually taken place and although it still conveys that sense it is also used as a descriptive word. That is how language changes. It is also common now to say ‘normalcy’ instead of ‘normality’ and ‘societal’ instead of ‘social’. In the case of the latter, the word ‘societal’ now refers to something relating to society as a whole as in ‘societal norms’. In the past ‘social problems’ would have meant problems in society as a whole but now this phrase would mean an individual’s problems in relating to society. Language is never static, it is constantly adapting and changing especially in times of technological advance and social change.

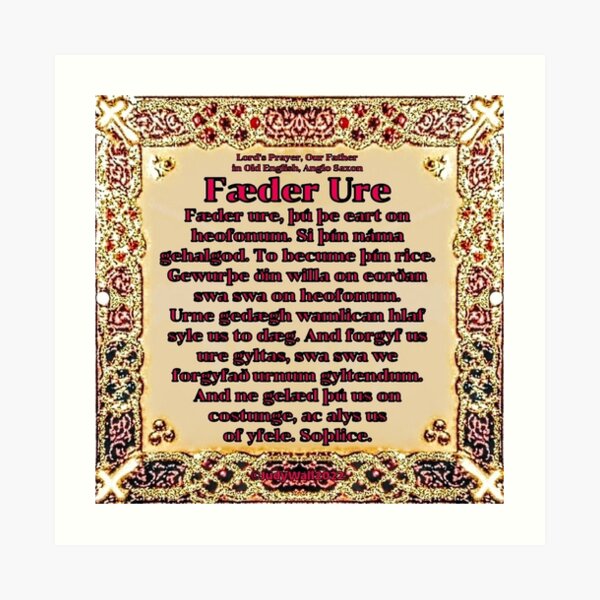

The Lord’s Prayer: A Text Through the Ages

The Bible has been translated into every possible language for many centuries, and so a comparison of a well known text shows how language has advanced. In the examples below, the meaning of the words and text has not changed but the language has evolved dramatically.

THE LORD’S PRAYER IN OLD ENGLISH (AD 995)

Fæder ūre

þū þē eart on heofonum

Sī þīn nama gehālgod

Tō becume þīn rice

Gewurþe þīn willa

On erðon swā swā on heofonum

Urne gedæghwamlīcan hlāf syle ūs tō dæg

And forgyf ūs ūre gyltas

Swā swā wē forgyfð ūrum gyltendum.

And ne gelæd þū ūs on costnunge

Ac alȳs ūs of yfele.

This may not even appear to be English! However, once we start to try to pronounce the words it is a little clearer. For example, ‘heofonum’ read aloud as ‘he-of-on-um’ does sound akin to the modern word ‘heaven’. Other words, such as ‘swa’ differs quite a lot from ‘as’.

You may notice some letters that we no longer use in modern English. Þ is called ‘thorn’ and is pronounced like the ‘th’ in ‘the’ or ‘these’. ð is called ‘eth’ and is pronounced as a hard ‘th’ as in the word ‘with’.

THE LORD’S PRAYER IN MIDDLE ENGLISH (Wyclffe’s Bible, 1389)

Oure fadir

That art in hevenes

Halwid be thi name

Thi kingdom come to

Be thi wille don

On erthe as in hevenes

Give to us this day oure bred ovir othir substaunce

And forgiv us oure dettis

As we forgiven oure dettours

And lede us not in to temptacioun

But delyevr us from yvel.

Once more, reading this text aloud will help. If you change a ‘d’ sound to ‘th’ you often arrive at modern English, for example ‘fadir’ does not sound far off ‘father’. This to do with the Germanic roots of English. Many German words use a ‘d’ which is a ‘th’ in English such as daar/there, drei/three, don/thorn.

‘Wille’ is not just a different spelling. The ‘e’ on the end would have been pronounced and so the word would have been spoken as ‘will-uh’.

‘Tempacioun’ is obviously ‘temptation’ in today’s English. ‘Cioun’ (or ‘tion’ is a standard suffix in Middle English, for example devocioun (devotion) and entencioun (intention), both found in Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale.

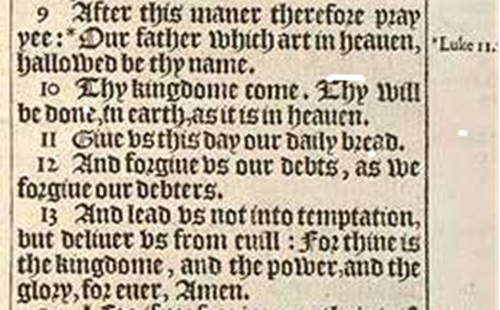

THE LORD’S PRAYER IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH (King James Bible, 1611)

Our father which art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come.

Thy will be done

in earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses

as we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

This is the most well known version today. It uses the familiar ‘you’ to address God, for examply ‘thy name’ rather than ‘your name’ Other than ‘Thy’ and ‘this day’ rather than ‘today’ it sounds very much like the language we speak and read today and is instantly comprehensible to a modern English speaker.

THE LORD’S PRAYER IN CONTEMPORARY MODERN ENGLISH (My translation, January 2024)

Our Father in Heaven,

May your name be holy.

Your kingdom come,

Your will be done on earth just like it is in Heaven.

Give us our daily bread today

And forgive our wrongs as we forgive those who wrong us.

Don’t lead us into temptation but deliver us from evil.

You will notice how much shorter the sentences are! The biggest change from Early Modern English

is probably the use of ‘your’ rather than ‘thy’. Contemporary modern English, unlike French or

German, does not differentiate between a formal and informal second person singular and so we

lose the sense that God is addressed in the informal, denoting a close relationship. This indicates the

way in which changes in language over time create changes in meaning of certain texts and phrases.

It is difficult to translate the Anglo-Saxon version into today’s English and maintain the same sense;

the closest I could have come to was to say ‘Our Dad who is in Heaven’ but that would be to change

the sense of the wrong word.

Famous Texts from Different Stages of the English Language

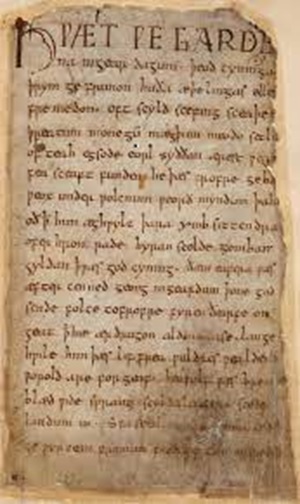

ANGLO-SAXON: BEOWULF

(Don’t worry if you can’t read this without a translation!)

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum,

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

Oft Scyld Scefing sceaþena þreatum,

monegum mægþum, meodosetla ofteah,

egsode eorlas. Syððan ærest wearð

feasceaft funden, he þæs frofre gebad,

weox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þah,

oðþæt him æghwylc þara ymbsittendra

ofer hronrade hyran scolde,

gomban gyldan. þæt wæs god cyning.

ðæm eafera wæs æfter cenned,

geong in geardum, þone god sende

folce to frofre; fyrenðearfe ongeat

þe hie ær drugon aldorlease

lange hwile. Him þæs liffrea,

wuldres wealdend, woroldare forgeaf;

Beowulf wæs breme blæd wide sprang,

Scyldes eafera Scedelandum in.

Swa sceal geong guma gode gewyrcean,

fromum feohgiftum on fæder bearme,

þæt hine on ylde eft gewunigen

wilgesiþas, þonne wig cume,

leode gelæsten; lofdædum sceal

in mægþa gehwære man geþeon.

Him ða Scyld gewat to gescæphwile

felahror feran on frean wære.

Hi hyne þa ætbæron to brimes faroðe,

swæse gesiþas, swa he selfa bæd,

þenden wordum weold wine Scyldinga;

leof landfruma lange ahte.

This is the beginning of the heroic poem Beowulf, which can be found on the Poetry Foundation as can its translation by Francis B. Gummere:

LO, praise of the prowess of people-kings

of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped,

we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!

Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes,

from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore,

awing the earls. Since erst he lay

friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him:

for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve,

till before him the folk, both far and near,

who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate,

gave him gifts: a good king he!

To him an heir was afterward born,

a son in his halls, whom heaven sent

to favor the folk, feeling their woe

that erst they had lacked an earl for leader

so long a while; the Lord endowed him,

the Wielder of Wonder, with world’s renown.

Famed was this Beowulf: far flew the boast of him,

son of Scyld, in the Scandian lands.

So becomes it a youth to quit him well

with his father’s friends, by fee and gift,

that to aid him, aged, in after days,

come warriors willing, should war draw nigh,

liegemen loyal: by lauded deeds

shall an earl have honor in every clan.

Forth he fared at the fated moment,

sturdy Scyld to the shelter of God.

Beowulf is a heroic poem, meaning that it follows the exploits of a warrior following the pre-Christian veneration of battle in Anglo-Saxon culture, but also combining Christian ideals as is seen in this opening passage.

The word ‘Hwæt’ at the start of the poem contains a dipthong (like a and e added together’ and is pronounced ‘hwet’. It’s is a bit like ‘ecce’ in Latin (the word which begins The Aeneid and other epic poems), here translated ‘Lo!’ (Behold!). It tells us that we are about to hear something literary. I say ‘hear’ rather than ‘read’ as Anglo-Saxon literature was passed down in an oral tradition. It so happened that some time between 975 and 1025 a monk recorded this story and the only remaining fragment of it forms part of the Nowell Codex, pictured below.

The work of producing a book in the Anglo-Saxon period was back breaking. It took place in monasteries which were the centres of learning and the arts of the period. Texts were written on velum, or sheep’s hide, and it took a herd of 300 sheep to produce one Bible. These sheep were raised by the monastery for that purpose. Inks were costly, with the most expensive colour being blue which was imported from Afghanistan and contained lapis lazuli. Yellow ink contained arsenic making writing with it a perilous task! Black ink was made using oak galls (acorns which had gone bad) mixed with soot. Quills were goose feathers cooked with hot sand poured into them to make them rigid enough to use for writing. Scribes often developed Scrivener’s Palsy (writer’s cramp), a debilitating arthritis of the hands.

The written documents we have from the Anglo-Saxon period were produced this way in monasteries and so the language which has been passed on is sacred and literary, rather than common every day speech. Some less poetic words have been preserved over the centuries to give us some of our most choice swear words, as mentioned earlier.

Learning Anglo-Saxon takes some time, but let’s look at a few interesting words from the text above.

Þeodcyninga

This begins with the now lost letter thorn, described above, and so this word is pronounced as ‘thay (hard TH) –od –coon –in –ga. Cyning = King. Cuniga = Kings. This is a much different way of creating a plural than we find in modern English. There were several different noun endings and ways to create a plural, which you can read about here.

The Germanic plural ‘en’ has survived in English in words like ‘children’ and ‘oxen’.

monegum mægþum

Old English poetry is alliterative rather than rhyming, and this is a great example. Gummere translates it as ‘many a tribe’. It more literally means ‘many mayweeds’. Idioms are a big part of the development of a language, afterall! One day people may wonder what on eath we mean when we talked about ‘damp squibs’ or ‘lame ducks’.

Gewunigen

To anyone with any familiarity with German, this is obviously a verb (to support, become acquainted with). The ge prefix and the en suffix tell us that this is an infinitive.

If you like swords, sorcery, monsters and adventure and don’t mind the fact that parts of the story are missing, you can read a free translation of Beowulf on Project Gutenberg.

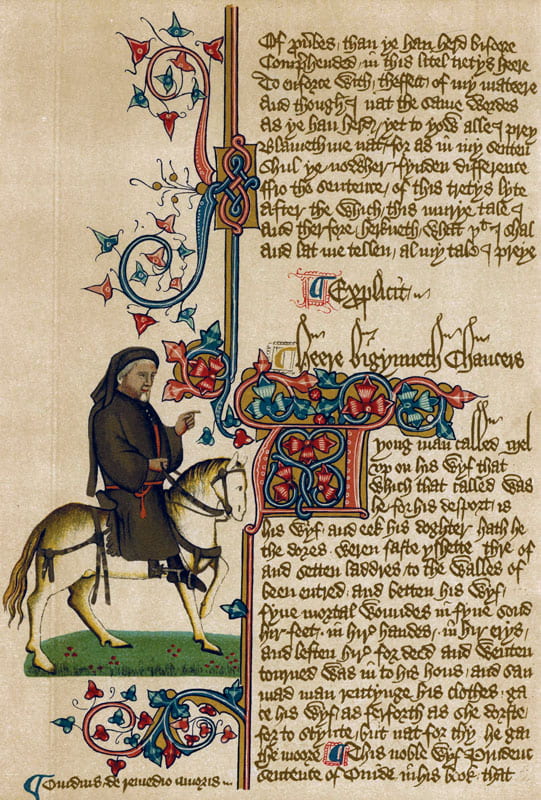

MIDDLE ENGLISH: THE PARDONER’S TALE

One of the most famous writers in Middle English is the civil servant Geoffrey Chaucer whose most famous work is The Canterbury Tales, which both tells the background stories of several pilgrims on their way to Canterbury and recounts stories told by the pilgrims. Monastic in tone this most certainly is not; the humour is bawdy and although Chaucer was himself a Christian the criticism of the business of pilgrimage is thinly veiled.

Here is an extract from a quite dark story, The Pardoner’s Tale. A pardoner was someone who sold religious relics (real or fake, what we might think of as spiritual knock offs).

Our Hoste gan to swere as he were wood,

‘Harrow!’ quod he, ‘by nayles and by blood![i].

This was a fals cherl and a fals Iustyse!

As shamful deeth as herte may devyse

Come to thise Iuges and hir advocats!

Algate this sely mayde is slayn, allas!

Allas! to dere boghte she beautee!

Wherfore I seye al day, as men may see,

That yiftes of fortune or of nature

Ben cause of deeth to many a creature.

Hir beautee was hir deeth, I dar wel sayn;

Allas! so pitously as she was slayn!

If you read this aloud, it may still be a little confusing but it probably makes a lot more sense than Beowulf.

Here is a modern English translation alongside the Middle English, taken from Harvard’s website.

Oure Hooste gan to swere as he were wood;

Our Host began to swear as if he was crazy;

288 “Harrow!” quod he, “by nayles and by blood!

“Alas!” said he, “by (Christ’s) nails and by (His) blood!

289 This was a fals cherl and a fals justise.

This was a false churl and a false judge.

290 As shameful deeth as herte may devyse

As shameful a death as heart can devise

291 Come to thise juges and hire advocatz!

Come to these judges and their advocates!

292 Algate this sely mayde is slayn, allas!

At any rate, this innocent maid is slain, alas!

293 Allas, to deere boughte she beautee!

Alas, too dearly she paid for her beauty!

294 Wherfore I seye al day that men may see

Therefore I say that every day men may see

295 That yiftes of Fortune and of Nature

That gifts of Fortune and of Nature

296 Been cause of deeth to many a creature.

Are cause of death to many a creature.

297 Hire beautee was hire deth, I dar wel sayn.

Her beauty was her death, I dare well say.

298 Allas, so pitously as she was slayn!

Alas, so pitifully as she was slain!

Some words are very easy to process, for example ‘hoost’ as ‘host’ and ‘nayles’ as ‘nails’. Others are little less clear, for example ‘hire’ (pronounced her-uh) meaning ‘her’ . ‘Sely’ is translated as ‘innocent’ and from it we get the word ‘silly’, showing how the connotations of words change over time.

‘Cherl’ is an interesting word coming from the Anglo-Saxon ‘ceorl’, the word for a lower class labourer from which we get our word ‘churlish’.

The text above which contains both the Middle English and Modern English version of the poem is probably the kind of text best used in learning to read Middle English. It clarifies the words and explains the words which have fallen out of use. It is also a good idea to read it aloud.

EARLY MODERN ENGLISH: SHAKESPEARE SONNET 18

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimmed.

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

This is much closer to today’s English. One of the most notable differences is the use of the informal second person singular, ‘Thou’ which we would render ‘you’.

The other significant difference is in the verbs, especially ‘hath’ which we would say as ‘has’. Let’s look at the verb ‘to have’ in the present tense in Early Modern English and Modern English.

| Early Modern English | Contemporary Modern English |

| I have | I have |

| Thou hast | You have |

| She/he hath | She/he has |

| We have | We have |

| You have | You Have |

| They hath | They have |

English verbs have become more simplified over time.

‘Owest’, ‘growest’ are elided for poetic reasons to ‘ow’st’ and ‘grow’st’. Let’s look at the verb ‘to grow’ in the present tense. It is a more standard verb than ‘to have’.

| Early Modern English | Contemporary Modern English |

| I grow | I grow |

| Thou growest | You grow |

| She/he groweth | She/he grows |

| We grow | We grow |

| You grow | You grow |

| They grow | They grow |

MODERN ENGLISH: PRIDE AND PREJUDICE

The opening lines of Jane Austen’s novel are some of the most famous in the English language. Let’s look a little at the language of the early nineteenth century and how it differs from the language we use today:

IT is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do not you want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

“What is his name?”

“Bingley.”

“Is he married or single?”

“Oh! single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!”

This conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet is very similar in its language to a conversation that might take place today, except some words may seem archaic to us. ‘Why, my dear’ is probably not a phrase we would use. We would probably say, ‘Well, my dear…’. Michaelmas is probably a bit of an arcane word now, too.

Dialects of English

Like any other language, English has many dialects. The former British Empire spread its use throughout the world and different turns of phrase and idioms are used in England, Scotland, Ireland, wales, India, America, Australia, Canada, New Zealand…

This it too huge a topic to deal with here but you have probably noticed some differences between English spoken in England and American English, for example I have been watching a TV show based in England where characters use the American phrase ‘wind up’ whereas an English person would more probably say ‘end up’. An American might say ‘I am getting mad’ whereas a British person would say, ‘I’m getting cross’.

Spelling is also different, for example ‘colour’ (English) and ‘color’ ,(American), ‘favourite (English) and ‘favorite’ (American). Johnston’s dictionary had less influence in the USA, it seems, plus an amalgamated population who initially spoke several languages were bound to change and adapt the language in most common use. This is how language changes and adapts.

I hope you have enjoyed this little foray into the evolution of the English language. Many books and course are available on the topic.

Please sign up to my mailing list for more articles like this one.