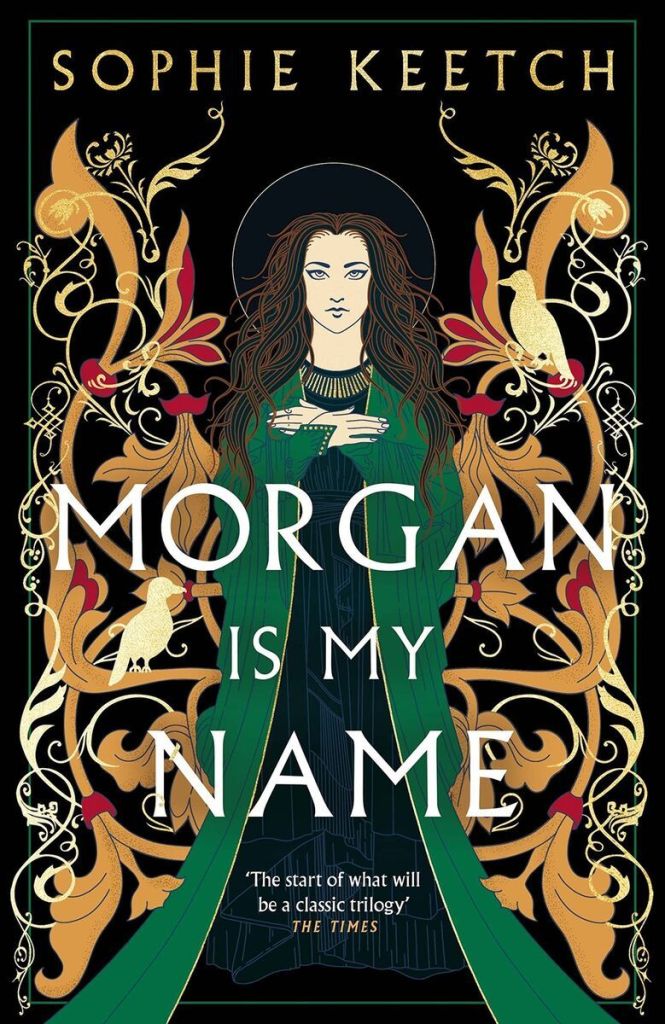

Morgan Is My Name by Sophie Keetch: Arthur’s Sister Before She Was le Fay

In my World Literature course, I lectured on how the figure of Morgan le Fay throughout her literary existence (dating back some 9 centuries) has a lot to teach us about changing attitudes to women, and changing attitudes generally. The character of Morgan (later given the epithet le Fay or fairy in fake French by Thomas Malory in 1485) first appeared in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini (Life of Merlin) in 1150 and so she is one of the oldest characters in the canon of Arthurian mythology. At first she appears as a healer and mystical benefactor, one of the 9 queens of Avalon who bear away Arthur’s body for healing after his final battle at Camlann. She maintained her magical powers and transitioned into an antagonist during the Lancelot-Grail Cycle and the Post Vulgate Cycle later in the medieval period.

It was Thomas Malory in his famous Morte D’Arthur (Death of Arthur) in 1485 who described her unequivocally as a villain and Arthur’s nemesis, loathing the Knights of the Round Table and especially reviling Guinevere. She reveals Guinevere and Lancelot’s affair, triggering events which lead to the fall of Arthur and his court. We last see her remorseful and grief stricken, bearing her brother to Avalon as she did in earlier versions of the story.

It must be pointed out that during the medieval and Renaissance periods she may have been a jealous sister using her powers for evil (witch hunts showed Europe’s attitudes to magic at the time), but she was never the mother of Mordred and so the harbinger of Arthur’s doom. That was her sister, Morgause. 1981’s Excalibur conflated Morgan and Morgause on screen in the character of Morgana, seductively played by Helen Mirren. That became a trend with 1998’s Merlin seeing a slightly pathetic Morgan (Helena Bonham Carter) controlled by the evil Queen Mab (Miranda Richardson), bearing Mordred to end the reign of Arthur.

From the femme fatale of the 1980s and 90s, in the 2000s she became motivated by power. Malory had described her as a usurper but this was taken further by the writers of the BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012) who make her the daughter of Uther Pendragon rather than of Igraine and Gorlois and so give her a claim to the throne should her brother die. It seems that a lust for power is more palatable for a 21st century audience than a lust for destruction and revenge. Starz also named her Morgan Pendragon in 2011 in the ill fated series Camelot.

Not all modern retellings see her as a villain. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1982 novel Mists of Avalon (a book I truly can’t stand) sees her as fighting the pagan cause against Christianity. Quite frankly, Zimmer Bradley’s heavy handed Christian bashing ruins any chance of her Morgan becoming a fully fleshed out figure. Keetch avoids falling into that trap: her convent educated Morgan is interested in knowledge and less in imposing her route to it upon other people. As she says, ‘Knowledge cannot be bad, only misused’.

My personal favourite Arthurian retelling, T.H. White’s The Once and Future King portrays her as a harmless if bitter eccentric with Morgause being the most notable half sister in Arthur’s story.

But it is Arthur’s story: a man’s story in which men make decisions and women are the subject of those decisions.

Morgan is My Name is an intriguing title: it seems to tell us immediately that this character is not the 1990s Morgana, a composite figure. It also takes pride in the Welsh associations with the name. Keetch’s Welsh heritage and her studies of Arthurian myths can be spotted throughout the text.

The name Morgan (Morgana, Morgain, Morgein) comes from the Old Breton for ‘sea born’, as Keetch makes clear at the start. Throughout the novel the sea and water is a metaphor for when things are going well for her (for example, her liaison with Accolon) and fire when she is angry or hurt, for example her final literally blazing row with Urien.

The obvious way in which her Morgan differs from the mythological character in this first part of a trilogy is that so far she hasn’t shown herself a sorceress. She revived a bird as a child and was able to detect Merlin’s nefarious spell which allowed her mother to be abused by Uther Pendragon, but unlike her BBC counterpart she is not continually throwing people against walls by waving her hand or setting fire to things with her eyes. Interestingly, she is able to summon fire when Merlin encourages her to look to the darker parts of herself, reinforcing the later Arthurian idea of Morgan as being capable of both good and evil. It also suggests that her road to magic will be a dark path undertaken in later instalments of the story. The lack of magic was, I confess, a little disappointing.

One thing that drew me to this novel was that it was shortlisted for the Times Historical Novel of the Year in 2023. Afterall, Morgan is a figure of myth, not of history. The novel does a great job of portraying the late medieval period in which Arthurian legend was popular. Edward III (1312-1377) was obsessed with King Arthur and the novel seems set in around his time, describing convents as centres of learning, the workings of an aristocratic household right down to which kind of birds would have been used in falconry by men and women and the functions of household staff and clerics, daily religious rites and devotion, patronage of religious establishments by wealthy ladies, the kind of clothes which would have been worn and many other aspects of medieval life, most strikingly the lack of freedom accorded to women and their use as political pawns if they happened to be born into the nobility. What is anachronistic is the mention of minor kings and kingdoms such as Lothian and Gore. All this is necessary to keep it Arthurian and it has been done before: the BBC’s Merlin is ostensibly set in the same period as is Disney’s take on T.H. White’s classic The Sword in the Stone.

Against this backdrop we see young Morgan aware of her mother’s deception by Merlin and Uther Pendragon, thrown into turmoil by the death of her father and her mother’s subsequent marriage to keep the family safe. She is unable to conceal her anger against the man who caused the death of her father and so is sent to a convent as a teenager where she is able to indulge in what she really loves: education. Her role as a scholar and healer has a basis in medieval texts but becomes the real core of her character here, as she tells her mother aged 8, ‘I want to learn everything’.

Her best friend and lady-in-waiting Alys and the servant Tressa serve to show the loyalty Morgan inspires in less privileged women but also that it is not only noble women who face limited choices. Tressa has been lucky to serve on the Tintagel estate and Alys as a lesser noble can either marry to advance her family or become a nun. Choosing life as a scholar goes hand in hand with a religious life. That is Morgan’s choice until Uther forces her hand and she marries the seemingly charming King Urien of Gore. As time goes by his charm fades into tyranny and violence, and even as a queen Morgan is trapped until she makes the decision to flee which requires careful strategy and not a little courage.

Overall, this novel bodes well for the rest of the trilogy with a sympathetic protagonist, just enough allusion to Arthurian myth to feel familiar and yet it keeps us guessing, and well drawn secondary characters. It will be interesting to see if her so far protective brother, King Arthur, remains a noble figure. Occasionally the language is not exactly literary, as in Morgan’s sexual encounter with Accolon which read like 50 Shades of Gray fan fiction but it did improve as the novel progressed. This is well worth a read as another instalment in the centuries old development of Morgan le Fay and an impressive debut from Sophie Keetch.

For more articles, the monthly Book Club and other events sign up to my mailing list here.